Stepping in a library is often a humbling and inspiring moment. As we enter through the door of the building an overwhelming feeling takes us as the World knowledge is facing us. The possibilities are endless and we are privileged enough to be there, the access at our finger tip. As this brief yet precious instant comes to pass we become pragmatic, looking for the front desk or trying to understand how to navigate the large building to find what we came here for, a specific book, some yet unknown books on a topic or finally just a place to sit, read and think. Rarely do we take the time to consider how the library itself is organized. We rely on the interface that is the librarian or even the computers available around in order to search through the catalog. What we quickly realize is that navigating randomly will only bring us so far and we must, finally, grasp some understanding of how this entire edifice is built in order to organize knowledge in a way that makes it accessible to us and all others patrons.

What is interesting is that libraries could be useless. Libraries make knowledge accessible but for the last few year that knowledge is usually produced in a digital format first. It can be copied, shared and browsed at a much lower cost than printed, stored in multiple physical buildings around the world and to be pragmatic spending more time unused than used. Yet, somehow libraries still exist and I would argue they are still extremely precious. What makes the library precious is both its habitat, its librarians and finally us its patrons. It is this active collision of needs that makes it valuable. What we actually look for by visiting a library is not the book we know we need but rather the ones next to it. It is the serendipity of trying to get a book that is not present anymore and sparking a conversation with someone else who just picked it. It is the unexpected recommendation from the librarian that is truthfully a better match than what we initially thought. The question then becomes, what sparks this serendipity that seems so difficult, if even possible, to reproduce online through a seemingly so convenient search box?

A library is a building, but what is deploying within that space is an algorithm. An algorithm designed by librarians, adjusted by its patrons through their usage and finally fitted within the boundaries of the walls of that building. That algorithm could for example be the Dewey Decimal Classification or something more specific like the National Library of Medicine classification or any of the numerous library classification systems established over the last centuries. The interaction with the building and the patrons is going to help the selection then adaptation of such a classification system. The selection is done through a set of criteria including for example: expressiveness, mnemonics affordances, hospitality, speed of updates and degree of support or consistency. Research exists comparing different classification system but overall there is no objective consensus on what is the better solution, only a solution that better fit explicit needs within a context. In turn libraries are going to accommodate for their patrons with, a naive example we all now, the latest arrivals prominently featured or some rare books as symbols that represent the culture and values of the library. Finally and the most interesting aspect for this reflection is that once an classification system has been established for a building putting the actual bookshelves in place and the books on them. The task in itself appears trivial if not mundane. What becomes fascinating is when the library receives a new book. Its position is well defined thanks to the hospitality criterium of the and yet, it does not fit!

In our library, the building obviously can not grow. The footprint is firmly established. It will surely be possible to somehow accommodate a few more but this simply can not be repeated numerous times. What will most likely happen is an exception in our algorithm. Namely a special case that despite the classification system working we have to use an incoherent solution. The most emblematic of these examples from an architectural viewpoint is probably the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Dominique Perrault received the 1996 European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture for this work. What makes it emblematic is that the 4 towers which represents opened books are prominent yet inaccessible to the public as they hold the book reserve. Such books are not, unlike those in the haut-de-jardin and rez-de-jardin levels, directly accessible and must thus be ordered a day in advance. Consequently what a passerby witness while looking at the building as the vastness of exceptions. The 22 stories towers are inaccessible except to very few librarians. One could argue that somehow the algorithm failed visibly more than it succeeded but constraints, starting with the volume available to the public in a city like Paris, are such that understandable compromises had to be made.

This begs the question though : what if a librarian could move walls around? What if instead accepting that compromise one would challenge it? Before even trying to answer it is worth coming back to why virtual architecture could be useful now, more than few years ago. A decade ago virtual reality (or VR for short) already existed, even 2 decades ago. What radically changed though is that the cost of a working, usable system has been divided by 100. What was until recently only available to public and private research centers able to spend 100 000EUR to have technicians install a cave system is now available at a random supermarket or online delivered the next day for 300EUR and fits within a backpack. What it means is that not only librarians can consider working with VR but also their patrons can practically visit that work from the comfort of their home or offices. This creates radically novel ways to consider what a library can be.

Now an immediate questions comes to mind. Why bother with a building, an habitat, a 3D model for content that is in fine flat? One can of course take a book and consider it, a 3D object but from a knowledge perspective it could just as well be a scroll or a parchment as long as the ability to navigate through its index remains. In fact today most of us are not heading to physical libraries but rather rely on their online interfaces or even prior to that to generic search engines hoping that a simple query will bring us just the knowledge we need. Here I will argue that in addition to serendipity we vastly underestimate how spatial our cognition is. A personal yet deeply striking experience is that I have not visited my high school libraries for decades. Yet I can confidently say that up the granite spiraling staircase, passing the front desk and 1 row of bookshelf to the right you were then able to find the encyclopedia (back when Wikipedia was not yet available). This is simply incredible to me. I somehow have trouble remembering key dates in history, of even the birthdays of acquaintances but navigating in space remains incredible memorable. Recent progresses in cognitive science have been able to pinpoint dedicated neurons which sole purpose is to position ourselves in space. Some of the most famous have been the grid cells, which as the name suggest allows us to establish our location within an abstract grid, the place cells, boundary cells, etc. There is in fact a whole set of cells dedicated to helping us and other mammals navigate efficiently through space. What is also particularly interesting is that this system also helps us to navigate through abstract spaces. Research in interfaces for knowledge management show us that, despite the common assumption, we truly do not prefer search to navigating a set of directories. Search is great when it works but when it fails, there is nothing helping to recover. Navigation though provides with every step potential landmarks help to activate memories and see if we are indeed or not down the right path. The affordability of VR headsets and this incredible ability to efficiently navigate and remember in space begs the question of how one could design a habitat for knowledge in space.

Even though this might seem initially abstract, most of us not being librarians, the impact is potentially much broader. Indeed even though we are not necessarily laying down millions of books within vast buildings we are though organizing thousands if not millions of files, especially if we take into consideration photographs, through our lives. We might not be librarians yet we still try, usually unknowingly, to select and apply such an algorithm that will make within our abstract space, more efficient and pleasant. What if we could be the librarians of our own collections? The question might appear naive at first, librarians are after all managing the World knowledge, but arguably from their perspective, no matter how large the collection it is only a fraction of what is available today and always a fraction of what will be available tomorrow. Consequently even though the scale might be different the principles are similar : we must learn to organize an ever growing collection so that each new item becomes an advantage rather than a burden within our set of constraints.

Designing spaces for VR is simultaneously similar and radically different from conceptualizing a physical building. The obvious differences being that the risks are radically lower and the permissions needed to do so are in consequences nonexistent. At worst a terribly designed virtual space might make someone visiting it nauseous but in no circumstance will a failing support actually endanger their life. Physics in fact is optional in VR or can even be partial. Some objects can exert gravity while others in the same space might not, or differently. This also means flying can be considered but simulating heat flow is literally pointless. Beyond “just” gravity one can go even deeper and consider non-euclidean spaces. In VR one can walk around as the space itself bends or adding teleportation portals. What is surprising is that the mind is flexible enough, thanks to what has been recently discovered as cognitive maps, to represent such spaces efficiently for navigation. This might seem unreasonably convoluted at first but what is interesting is that abstract concepts like a navigating through a social network as a graph or a hierarchy seems to use the same mechanisms. Consequently it means the design of an abstract space, based on the algorithm of a classification system, might benefit from our very flexible abilities to represent any space. So much more remain to be explored, from the technical concept of map in mathematics to the poetic idea that coastlines with their fractal dimensions could somehow accommodate for Borges’ Library of Babel. These few examples hopefully become very exciting but it also means new design principles to navigate this vaster landscape of potentials must be written.

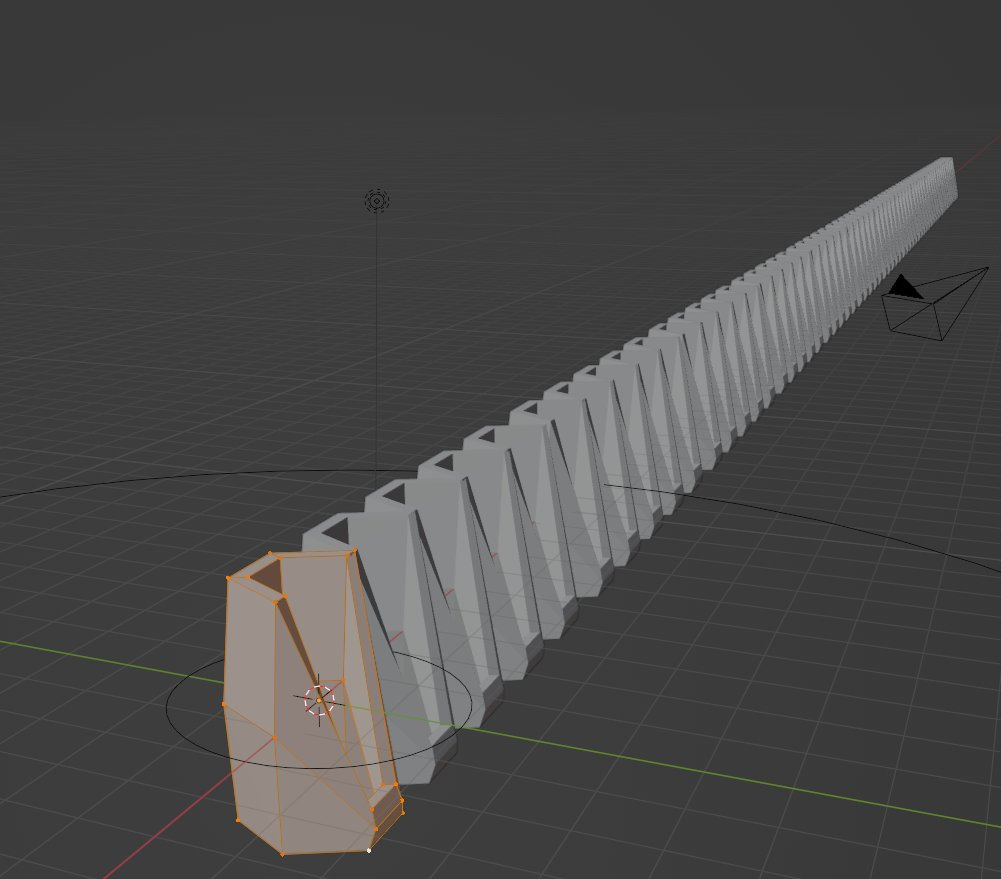

One crucial challenge of using an algorithm to spatialize information is temporal stability. Indeed one of the most famous of such algorithms is the force-directed graph where the nodes of a graph repulse each other until it becomes, hopefully, stable enough. The visualization is quite popular because it disentangles complex graphs, like a collection of books referencing each other is. What makes this practically unusable in this context though is that a single new node might change the entire layout. Even though visually impressive it makes navigation over time impossible to remember. The lack of stability over time means that with item added, one must start anew. A straightforward solution is to extend in a direction, for example always adding upward, but this in turns creates challenges of navigation and also of repetition like an endless corridor. Somewhere in between and potentially using some of the radically new perspectives shared before probably lies interesting solutions to explore.

Finally, once we reconsider an algorithm as a classification system, adjusted by usage and fitted within the boundaries of the walls of a virtual space, the question of moving walls in VR becomes a practical one. What was initially a fantasist question hopefully begs pragmatic answers. We, as the librarians of our collections, should consider how we can navigate efficiently what is to us the most precious, think about how it will change our ability to remember and finally support the creation of new knowledge.

Illustrations

Fractal bookshelf in Blender for procedural generation and later integration in Mozilla Hubs

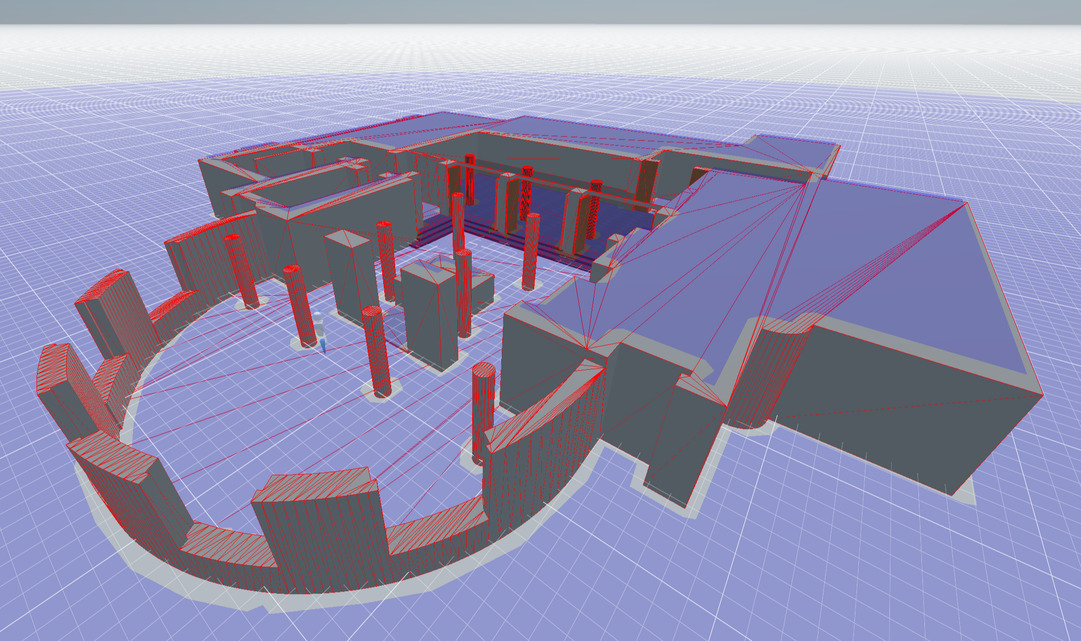

Visualization of the walkable area in Mozilla Spoke

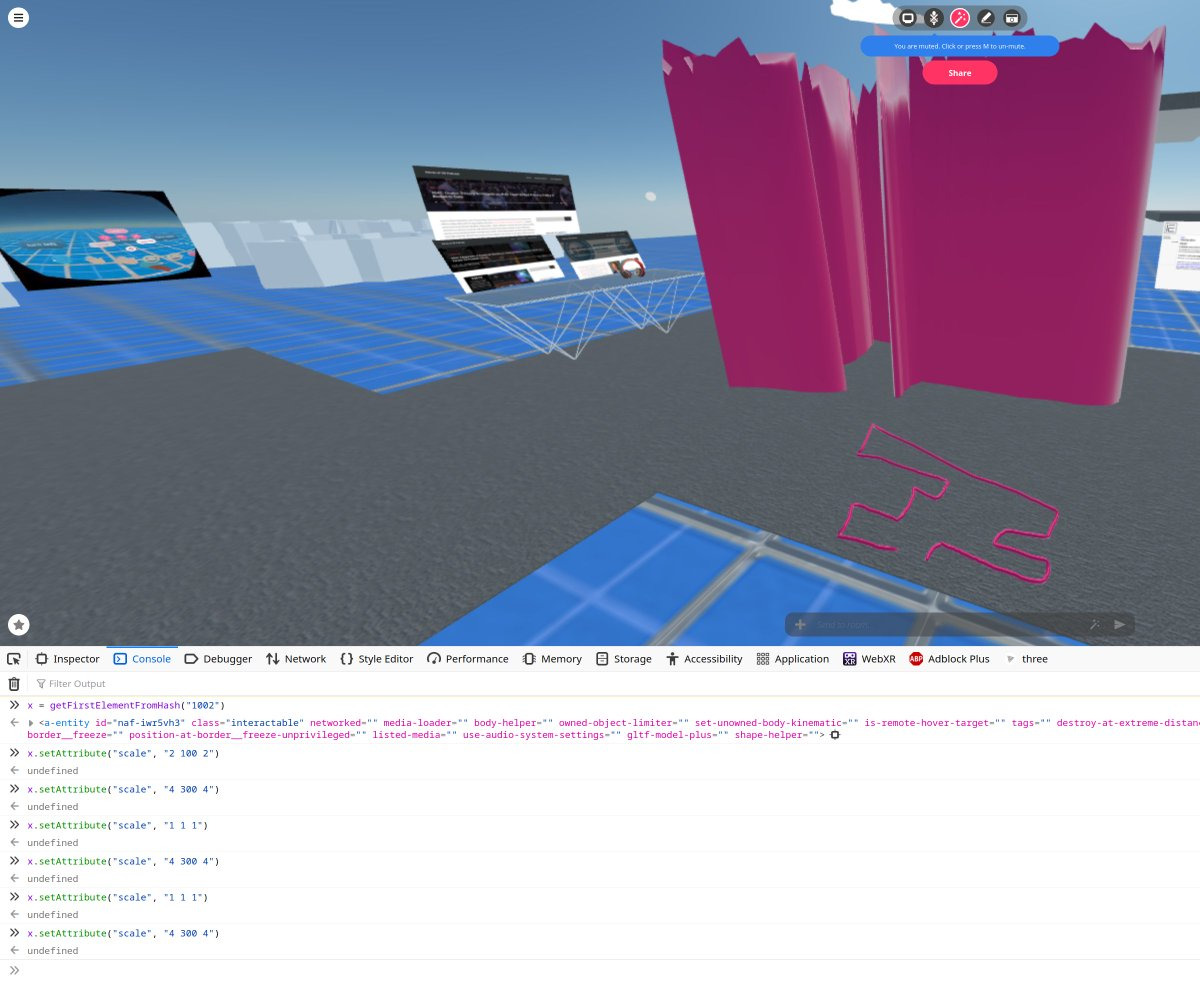

Exploration of documentation manipulation across scale, visual prototype, Collaboration with Thomas van Bouwel

Live testing of extrusion drawn in VR, customized Mozilla Hubs, Collaboration with Kent Bye

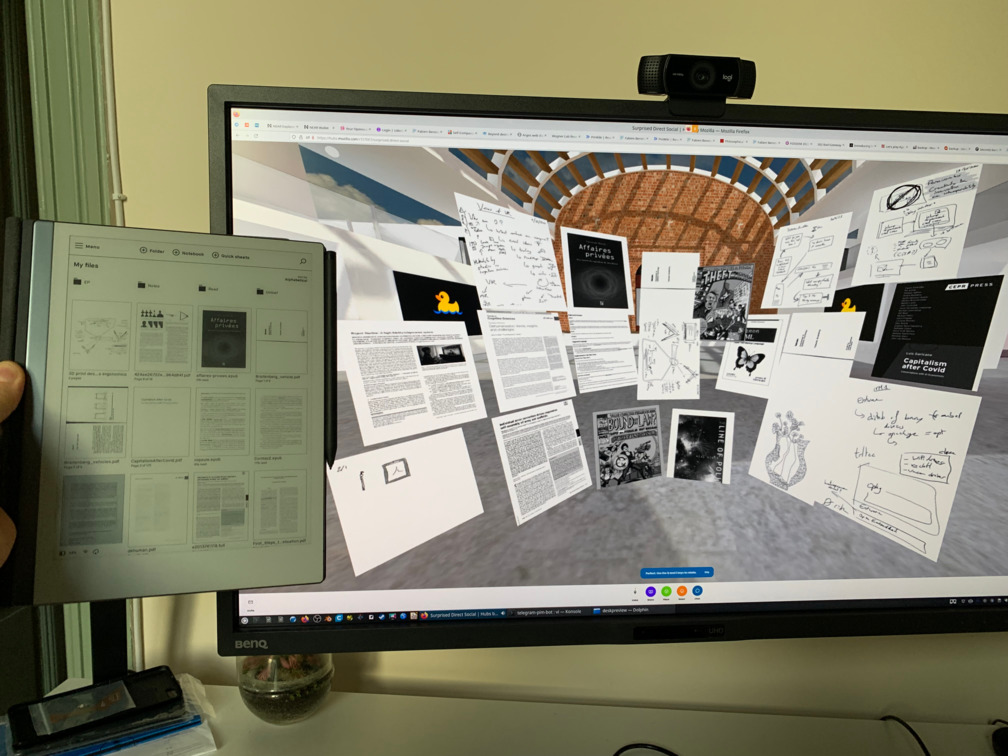

Triage of proceedings from IEEEVR2020 with a participant on desktop via webcam and another in VR, customized Mozilla Hubs

Live synchronization between a non spacial device (e-ink device to read and sketch) layout in a spacial environment, customized Mozilla Hubs

References

- Making CodeCity evolve

- The rise and fall of Cybernetics as seen in the evolution of the Dewey decimal system

- Dom Hans van der Laan, A House for the Mind

- Vi Hart and M Eifler (EleVR), Fun With Hyperbolic Space

- Design process in architecture

- Generative design

- Durable memories and efficient neural coding through mnemonic training using the method of loci, Wagner et al.

- What Is a Cognitive Map? Organizing Knowledge for Flexible Behavior

- Structuring Knowledge with Cognitive Maps and Cognitive Graphs

- Cognitive map–based navigation in wild bats revealed by a new high-throughput tracking system

- The ontogeny of a mammalian cognitive map in the real world

- Why is navigation the preferred PIM retrieval method? In The Science of Managing Our Digital Stuff

- Les objects dans l'espace, la planification dans l'action, B. Conein, E. Jacopin, (Raisons Pratiques 1993)

- Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne Atlas

- Paul Otlet, Traité de documentation

- Andy Clark, Supersizing the Mind

- Dewey Decimal Classification

- Edsger W. Dijkstra, EWD-numbered typescripts and manuscripts

- Carnes/Marchand-Zanartu, Images de Pensees

- Vannevar Bush, Memex

- Ted Nelson, Project Xanadu

- VR & Philosophy #04: A VR Wikipedia with Fabien Benetou

Considerations since submission

Physical books for Future of Text presentations

- 9781838665593

- 9782501130530

(more to be added soon from phone photos of barcodes)

Note that could also be a specific format, e.g JSON, in order to be manageable in a WebXR experiment also e.g

references:["value":9781838665593,"style":"ISBN"},{"value":9782501130530,"style":"ISBN"}]

This would also support other styles, e.g DOI, but also direct ones, i.e URL.

Note that as @references@ is on its own line it could be parsed from ?action=source.

Fabien Benetou's PIM

Fabien Benetou's PIM